CBNRM in southern Africa

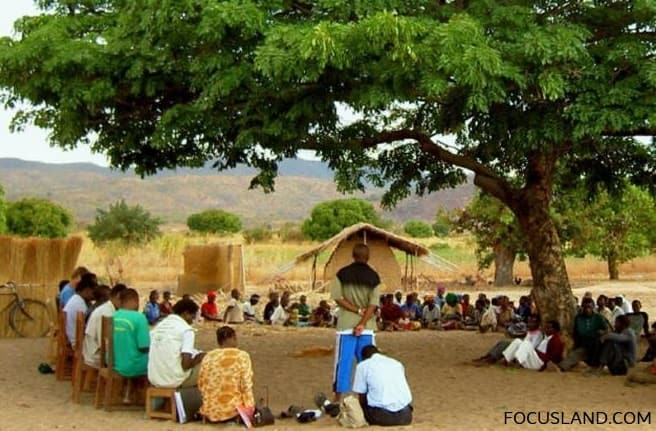

Community-based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) has been implemented in several southern African with various degrees of success. While the form in which CBNRM is implemented also varies from country to country, three main components to the conceptualisation of CBNRM in southern Africa can be identified (Jones and Murphree 2004):

1. In order to take management decisions, communities need rights over their land and resources, so that they can control access to resources and how they are used. They also need security of tenure i.e. the knowledge that these rights will not be arbitrarily removed by government and are secure over time.

2. Again in order to take management decisions and in order to manage the distribution of benefits, communities need representative and accountable institutions.

3. Communities must be able to derive appropriate benefits from the resources they are managing. They will be unlikely to invest time, effort and finances into managing a resource if the benefits of management do not exceed the costs.

This conceptualisation places CBNRM firmly in the space of rights-based approaches to conservation.

Best practice in providing the enabling conditions for CBNRM

CBNRM in southern Africa has focused on devolving rights over natural resources to local communities. This devolution has been most successful where it has been implemented through legislation rather than government policy decrees. There are some key considerations in developing such legislation, particularly security of tenure and flexibility.

Security of tenure over rights is a crucial component in providing the enabling conditions for CBNRM. Lindsay (1998) suggests the following as important elements of security of tenure that legislation needs to incorporate:

Clarity as to what the rights are in terms of use, decision-making and benefits: The law should provide clear definition of property rights and not vague phrases such as “the right to manage”

Certainty that rights cannot be taken away or changed arbitrarily: The conditions for removing rights given to communities must be fair and clearly articulated, and the issue of compensation should be addressed.

The duration of the rights must be articulated and must be long enough for benefits of use to be fully realised: Short or unspecified duration of rights will not instil confidence that time and effort can be invested in managing the resource with a realistic expectation of generating lasting benefits.

Rights must be enforceable against the state: The legal system must recognise an obligation on the part of the state to respect rights devolved to communities.

Rights must be exclusive: The holders of rights need to be able to exclude or control access to the resource by outsiders, otherwise there is no incentive for managing the resource as others can deplete it without sanction. Government needs to assist in the enforcement of group rights from outside interference. Exclusivity implies that the boundaries of the resource to which the rights apply must be clear, and there must be a defined group of users to whom the rights apply.

The law must recognise the holder of the rights: The law should provide a way for the holder of the rights to acquire a legal personality, with the ability to apply for loans, enter into contracts, collect fees, etc.

Commentators also suggest that enabling legislation for CBNRM should not be prescriptive about local institutional arrangements, but should be as flexible as possible to accommodate local realities and institutions and to provide legal space for meaningful choice by communities in how they arrange their affairs. Lindsay (1998) suggests three important aspects of flexibility:

Legislation should allow flexibility in deciding what the objectives of management should be and the rules that will be used to achieve those objectives: local resource users need to design management regimes that reflect the local status and circumstances of the resource and the benefits that the users seek.

Flexibility is required in how state law recognises user groups: The law should not prescribe the detailed structure of local organisations and the rules by which they operate. If the law tries to create institutions that are too complex or alien to local situations and tries to standardise institutions across different social settings, it is likely that these institutions will have little local legitimacy.

Flexibility is needed in the definition of management groups and areas of jurisdiction: A fluid method of defining the responsible group creates the possibility of finding those institutions and people who wish to cooperate in managing natural resources – the emphasis needs to be on self-definition.

Two countries that have taken a strong legislative approach to CBNRM are Namibia and Mozambique. To a large extent the laws enacted by both countries follow the principles set out by Lindsay.

CBNRM in Namibia

In 1996, the Namibian Government introduced legislation that gave local communities rights over wildlife and tourism on their land, if they form a management institution called a conservancy. The Nature Conservation Amendment Act 5 of 1996 enables the Minister to register a conservancy if it has the following:

a representative committee

a legally compliant constitution, which provides for the sustainable management and utilisation of game in the conservancy

the ability to manage funds

an approved method for the equitable distribution of benefits to members of the community

defined boundaries

Once the registration of a conservancy is published in the Government Gazette, the conservancy gains the “ownership” of hunt-able game (see below) which means the conservancy can hunt these species for its own use without permit or quota from government. The conservancy also qualifies for use rights through permitting and quota systems to capture and sell game and carry out trophy hunting.

The conservancy approach can be viewed as rights-based in the sense that the rights and obligations of local communities with regard to wildlife and tourism are entrenched in legislation. The area of land delimited by the conservancy boundaries is officially declared and the boundaries recorded in the Government Gazette. In summary conservancies gain the following use rights:

The conservancy can use hunt-able game (oryx, springbok, kudu, warthog, buffalo and bush pig), as it wishes for its own use.

The conservancy can enter into a contract for a trophy hunting company to buy the conservancy’s trophy hunting quota.

The conservancy can enter into a contract for a tourism company to develop a lodge or lodges and other tourism facilities.

The conservancy can suggest trophy hunting and other quotas to MET, but MET must approve the quota. In order to make quota proposals, the conservancy needs to monitor its wildlife and be aware of numbers and population trends.

The conservancy (or at least individuals within the conservancy) can shoot most problem animals if necessary without a permit, except for elephants and hippo.

If a conservancy wants to reduce wildlife numbers in order to reduce competition with livestock in time of drought it can reduce the numbers of hunt-able game if the meat, hides etc. are for own use. It can also apply to MET for a permit for removal of other species because of drought.

The conservancy can apply to MET for a permit to carry out other forms of game utilisation, such as live capture and sale of wildlife or the use of protected species.

The conservancy receives all income directly from its tourism and wildlife activities and does not receive this income from the state or have to share it with the state.

Conservancies decide how to use their income with no interference from the state, though government recommends 50% of income from tourism or hunting concessions should be allocated to community development projects

The Namibian conservancy programme has sometimes been criticised for being top down because it is based on government legislation that sets certain conditions and prescribes certain actions. However, as Lindsay (1998) suggests: “local management initiatives need state law, often more than their advocates like to recognise though usually less than governments are willing to admit”.

The Namibian legislation came about from the development of a shared vision for conservation and a request from communities to be able to benefit from the wildlife on their land. The approach was in fact demand driven. According to IRDNC (2011:40): “A solid case for meaningful policy change was created through broad-based consultation and negotiation through socio-ecological surveys conducted after Independence”.

The rights conferred on Namibian conservancies are not administrative privileges that can be arbitrarily removed, but are rights that can be defended in court. Although the rights are conditional, the legislation contains clear and transparent procedures for government to withdraw the rights. Although the rights are limited and government retains certain areas of decision-making, the Nature Conservation Amendment Act of 1996 assigns clear authority and responsibility to conservancies for certain decisions. The rights are exclusive to the members of the conservancy within the boundaries of the conservancy. The Act provides for the conservancy as a legally constituted body that can enter into contracts and acquire and dispose of property and receive fees and sue or be sued.

The Act is prescriptive in the sense that communities must form a new institution – the conservancy – in order to gain rights and through determining that conservancy constitutions must include the objective of sustainable utilisation and management of wildlife. The Act and accompanying regulations also prescribe certain elements that must be contained in conservancy constitutions to address governance issues such as financial management and accountability of conservancy committees to members.

However, the legislation demonstrates flexibility in enabling conservancies to craft constitutions that meet their own needs and objectives, and crucially in allowing communities to define themselves, and negotiate their boundaries with neighbours. It does not use existing government administrative boundaries as the means for defining a “community”, nor were biological boundaries used to define conservancies based upon the needs of wildlife. Rather, it was recognized that social boundaries were more conducive to the creation of a cohesive group of resource managers.

CBNRM in Mozambique

For a long time community-based natural resource management initiatives in Mozambique existed without strong legal backing from government. However two major changes in legislation have considerably strengthened community rights to land and natural resources.

The Mozambican Land law of 1997 provides for individuals, families and communities to acquire a land right certified by the state. The law allows for the simple delimitation of land by local communities and individuals. The use rights (not ownership) are known by the Portuguese acronym ‘DUAT’ (Direito de Uso e Aproveitamento da Terra). There has been a two-step process of first delimiting the community’s collective rights, and then delimiting family rights within the community, providing tenure security for communities and families (Norfolk et al 2020).

Recognition of community land rights through the DUAT is important for agricultural and other investors who wish to develop community land. The DUAT provides clarity regarding who the investor must negotiate with and communities and families can agree on whether to cede land to an investor or enter into a contract for the use of their land.

Norfolk et al (2020) identify some key lessons from the Mozambican land delimitation process:

A community land delimitation process is a vital precursor to securing and documenting of rights to individual family and household parcels. The delimitation of community boundaries, leading to government registration and issue of a formal DUAT certificate in the name of the local community, allows the community to assert a collective role in allocating and managing those rights.

Community land delimitation needs to be rooted in traditional organisation of social authority, settlement and land use, and the interpretation of ‘local community’ in that context. The boundaries should mirror the local, customary land administration and land management powers and responsibilities.

The delimitation process is an opportunity for institutional capacity-building. It can help community members to understand their rights and responsibilities vis-à-vis a range of external actors, including the state, private sector investors and neighbouring communities.

Entities with independent legal personality can represent the community in negotiation of land access with outsiders. A community land association endowed with legal personality represents the community as a private entity holding a collective land use right, in its dealings with the outside world. It can engage in negotiations with government or investors who want to access land.

In 2017 the Mozambican Government introduced a new Conservation law with accompanying regulations that provide for a category of Community Conservation Area as part of the formal protected area system. According to the Conservation Law 5/2017, a community conservation area is an area of conservation of sustainable use in the Community public domain, under the management of one or more local communities where they have the right to use and benefit from land, for the conservation of fauna and flora and sustainable use of natural resources.

The objectives of CCAs are to:

a) protect and conserve the natural resources existing in customary use of the community, including conserve natural resources, sacred forests and other sites of historical, religious, spiritual and cultural use for the local community;

b) ensure the sustainable management of the natural resources to promote local sustainable development;

c) ensure access and perpetuity of medicinal plants used by community members and biological diversity in general.

To form a CCA, the community must first obtain a DUAT under the Land Law of 1997. It must also demonstrate the consent of its members for forming the CCA, provide geographic boundaries of the CCA, provide an initial management plan for the area and a constitution of the management entity for the area. Under the legislation communities are able to define themselves. According to the law, in a CCA, the community can enter into agreements and contracts with the private sector for the commercial use of natural resources and charge use fees which accrue directly to the community. This provides communities with the opportunity to earn more income than the 20% of government use fees that go to communities in non CCA areas. This in turn can increase the incentives at community level for sustainable use of natural resources and improved local management. It can provide the resources necessary for communities to reinvest income in conservation management rather than being passive recipients of income from government.

One of the major gaps in the CBNRM approach in southern Africa has been reluctance by government to provide clear community collective land rights as well as resource rights. Namibia has provided communities with rights over natural resources, but not over land. The Mozambican land law provided land rights without clear rights over natural resources. However, combined with a DUAT, the formation of a CCA provides Mozambican communities with strong exclusion rights and control over their land and natural resources.

References:

IRDNC. 2011. Lessons from the Field: IRDNC’s experience in Namibia. Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation. Windhoek.

Jones, B. T. B., and Murphree, M. W. 2004. Community-based Natural Resource Management as a Conservation Mechanism: Lessons and Directions. In: Child, B. (ed). Parks in transition: Biodiversity, rural development and the bottom line. Earthscan. London. pp 63-103.

Lindsay, J. 1998. “Designing Legal Space: Law as an enabling tool in community-based management”. Presented at the World Bank International CBNRM Workshop. Washington, D.C., May 1998.

Norfolk, S., Quan, J., Dan Mullins, D. 2020. Options for Securing Tenure and Documenting Land Rights in Mozambique: A Land Policy & Practice Brief. A LEGEND publication. Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich. Chatham, UK.